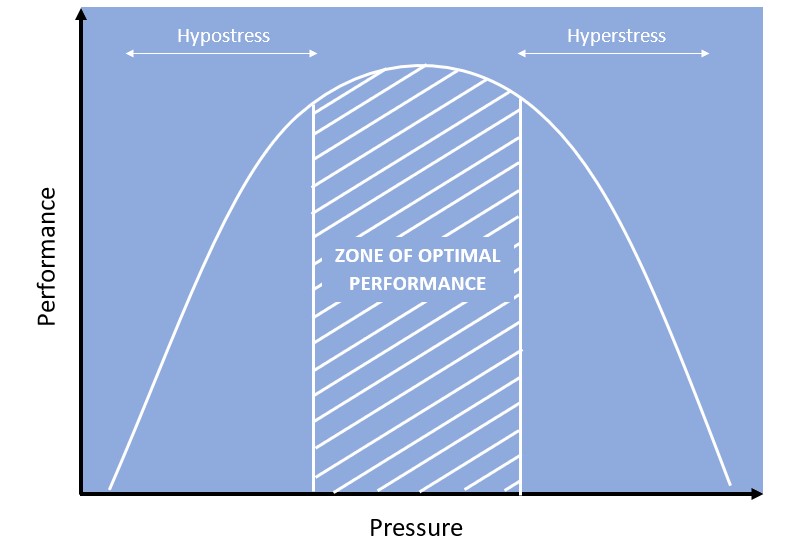

Figure 1 — The relationship between pressure and performance is represented by the Inverted-U Curve in the field of psychology.

With this being my second post, I found it fitting to investigate the Sophomore Slump: the idea that a second effort won't live up to the hype of the first. Let's uncover why they're so goddamn difficult to get right.

The Slump Side To Success

The short answer to why we slump post-success is, well... success. Success is the perfect storm of being great at what you do AND being acknowledged for it. However, the thing about storms (and attention spans) is that they're short-lived. So when the wind and rain of recognition die down, all that's left is you, your skill, expectations, and flowers of new people around you, all looking to get their sliver of sunshine. Without all the superfluous shit: success introduces a pedestal to fall from and 'yes men', both of which work against second effort success for reasons backed by psychology.

The Inverted-U Theory

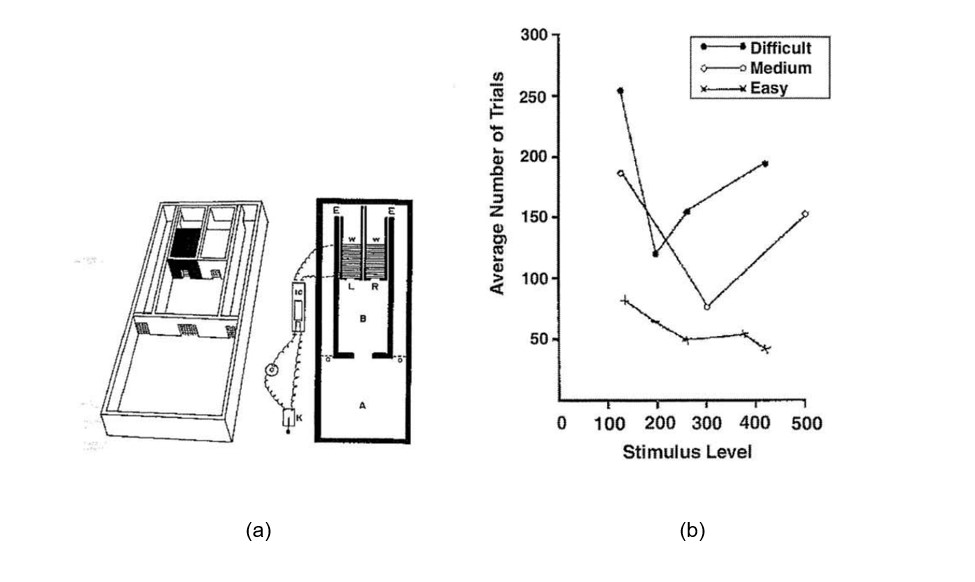

Back in 1908, psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson conducted an experiment in which mice travelled through one of two passages under varying light conditions (Fig. 2a). Each time a mouse chose the wrong passage, it was shocked to be made aware of its mistake until it reliably selected the shock-free path. What Yerkes and Dodson found was that as it became more difficult for the mice to choose the correct passage due to the dimmed light conditions, the stimulus or shock level required to cause a change in behavior approached a threshold (Fig. 2b). A low shock level didn't provide enough negative reinforcement to instigate a change in passage selection, while a high shock level provided too much negative reinforcement, hindering mice from making the right choice. Yerkes and Dodson dubbed this phenomenon the Inverted-U Theory, concluding there exists a stimulus sweet spot, between high and low levels of stimuli, that yields optimal performance. This same phenomenon, the Inverted-U Theory, explains the Sophomore Slump.

Figure 2 — (a) Shows the experimental setup for the study done by Yerkes & Dodson (b) Shows the data obtained from the experiment where the x-axis is the scaled shock level and the y-axis is the number of trials needed to form the habit of choosing the correct passageway.

The Pedestal Problem

One reason we slump is expectation. When you succeed, the new baseline for success becomes what you've just achieved. So, to be successful again, you have to match or even best what you've already accomplished. Add on top of that the natural inclination to fear the loss of the success you've just earned, and the stress of expectation becomes a detterent to performance as evidenced by the right-hand-side of the Inverted-U Curve (Fig. 1).

'Yes Men' Mayhem

Success changes how people percieve you. Some are inspired by your success, while others view it as an opportunity. These opportunists are called 'yes men' and they agree with or fail to question anything and everything you do to get in on the success they didn't achieve. And when 'yes men' are around long enough, you start living in an echo chamber. No conflict. No stress. Just a fed false consensus bias that kills drive, competitive edge, and ultimately the success you once had, as shown by the left-hand-side of the Inverted-U Curve (Fig. 1).

The Sophomore Slump Solution

The solution to the Sophomore Slump is this: experience just the right amount of stress to land smack dab in the middle of the Inverted-U Curve. Simple, straightforward, yet elusive despite having the perfect example all around us — terrible two-year-olds. Yeah, I'm talking about the rascals who throw tantrums in the middle of the grocery aisle, the mischief-makers who chuck pacifiers at people walking by, and the up-to-no-good kids who try to make a run for it with seriously underdeveloped motor skills. Yes, those two-year-olds. Sure they're misbehaved and annoying, but they're also brave for putting themselves in new, stressful situations, they're independent for not listening to what they're told, and they're resilient for failing and trying again. They're two and they've got nothing to lose. And when you're not succeeding, neither do you. So, be like a two-year-old. Be terrible. Because when you're terrible, there's no pedestal to fall from or 'yes men' around to feed you phony shit, no stakes or group-think, there's just you, your skill, and nowhere to go but up.

Tapping into my inner two-year-old,

The Monochrome Man